Fitness

When Assessing Presidential Fitness, Consider Racism

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Donald Trump’s “Black jobs” comment is a reminder of his long history of racism.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic:

A History of Racism

It will take years, and probably some history books, to fully deconstruct CNN’s Debate From Hell and its consequences. People are (understandably) focused on President Joe Biden’s alarming performance, but that preoccupation has gotten in the way of crucial analysis of the debate’s substance. So let’s excavate a short phrase that’s disturbingly illuminating: “Black jobs.”

“The fact is that [Biden’s] big kill on the Black people is the millions of people that he’s allowed to come in through the border,” Donald Trump said in response to a question first posed to Biden about Black Americans who are dissatisfied with him. “They’re taking Black jobs now. And it could be 18, it could be 19 and even 20 million people. They’re taking Black jobs, and they’re taking Hispanic jobs. And you haven’t seen it yet, but you’re going to see something that’s going to be the worst in our history.”

What exactly is a “Black job,” you may wonder? Trump did not say. But the archaic implication that there are some jobs that are just for Black people, or just for Hispanic people, certainly stood out to many Americans who were listening. (“It is the most racist statement that he’s made in the last three days,” Al Sharpton said in an interview after the debate.)

Even Trump’s claims about Black unemployment and immigration statistics are wrong. In fact, unemployment has reached historic lows among Black people during the Biden administration, and wage growth for Black workers and Hispanic workers has grown tremendously in that same period. Also, there are about 11 million undocumented immigrants in America, and no modern president has successfully addressed the complexities at the border.

Trump’s racism over the years has been well documented, and it did not slow down during his presidency. He attacked Black politicians and athletes as unintelligent and “low-IQ”; he expressed a preference for immigrants from Norway as opposed to Haiti and African nations, which he branded “shithole countries.” Later, as an ex-president, he used terms such as “racist” and “animal” to describe the Black prosecutors building criminal and civil cases against him and his business.

Since he left office, his bigotry, overt and implied, has only gotten worse. Just in the past month, Trump has claimed that his Black and Hispanic support “skyrocketed” as a result of his “amazing” mug shot, “the No. 1 mug shot of all time”—implying that Black people related to his status as an accused criminal. (That wasn’t the first time he bragged that his indictments had attracted Black voters.)

He has called Milwaukee, a majority-Black and majority-Hispanic city that’s hosting the Republican National Convention this month, a “horrible” city. His spokesperson later said that he was responding to a question about “increased crime” (although crime rates in Milwaukee are down this year) and “election fraud” (though investigators deemed all of Trump’s voting-fraud claims unfounded). But this is part of a larger pattern. He has also asserted without evidence that voter malfeasance is rampant in Philadelphia, where at least half of the population is Black or Hispanic.

The Trump effect is visible in his wider orbit too: His onetime lawyer Rudy Giuliani recently called Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis “Fani the ho” at a far-right Christian-nationalist event, eliciting whooping applause. And Trump has created an environment in which nearly 200 House Republicans felt comfortable voting to restore to Arlington National Cemetery a Confederate monument that included bronze figures of what the cemetery calls “an enslaved woman depicted as a ‘Mammy,’ holding the infant child of a white officer, and an enslaved man following his owner to war.” (The vote failed, and the monument will remain in storage.)

There was also the TV producer Bill Pruitt’s May 30 account in Slate of his time on the first season of The Apprentice, which aired in 2004. He described Trump calling a contestant the N-word in a conversation that Pruitt says was recorded. The group was discussing the merits of two finalists when someone said that one of them, Kwame Jackson, had overcome more obstacles than the other.

“Yeah,” [Trump] says to no one in particular, “but, I mean, would America buy a n— winning?”

Trump’s campaign has denied that this ever happened. But as The Atlantic’s Megan Garber recently wrote, Americans already know Trump’s racist record: “Trump has treated racism as a campaign message and a marketing ploy. He keeps finding new ways to insist that some Americans are more American than others. Epithets, for him, are a way of life. What could words convey that his actions haven’t? What, precisely, remains to be proved?”

And so, against this pattern of the past few weeks and decades, all the way back to a 1973 federal lawsuit charging Trump, his father, and their company with discriminating against prospective Black apartment renters (they settled the case and did not admit guilt), comes “Black jobs.”

A flustered Senator Marco Rubio, one of four men of color being floated as possible Trump running mates, tried on CBS to talk around those two words; he eventually said that Trump was referring to “working-class jobs.” Ben Carson, a retired neurosurgeon, Trump’s onetime Housing secretary, and another short-lister for the vice presidency, was more blunt. Trump was talking about “people at the lower end of the economic scale” doing “unskilled jobs,” he told CNN, adding that Trump “probably” could have phrased it better.

No kidding. One striking response to Trump’s casual stereotyping showed three smiling men in uniforms. “A physician. An astronaut. And a fighter pilot,” the caption of the X post read. “Reporting live from our #blackjobs.” Many of us have noticed that Barack Obama’s “Black job” was the presidency. And, as of 2021, the vice presidency is also a “Black job.”

As Trump tries to make inroads with Black voters, has his “Black jobs” comment hurt him? Perhaps: A postdebate CBS News/YouGov poll found that although registered voters overall gave the win to Trump—56 percent to Biden’s 16 percent—Black registered voters said, 39 percent to 25 percent, that Biden outperformed Trump. In another postdebate poll, by Data for Progress, which asked likely voters whom they would choose if the election were held tomorrow, Biden beat Trump 67 percent to 23 percent among Black voters, with 10 percent undecided. Still, that would be the highest share of Black-voter support for a Republican in more than 60 years, as Stephanie McCrummen reported in The Atlantic.

At a moment when Americans are preoccupied with questions of presidential fitness, it would serve all of us well to remember what the Trump presidency looked and sounded like—and whom it excluded.

This is the white noise of the 2024 campaign and, sometimes, the blaring Klaxon. Trump’s goals are to win the White House, kill the federal cases against him, and stay out of prison. He may pick a vice president of color if he thinks it will help him. But that won’t mean that Trump and his MAGA movement have grown, changed, or made sudden peace with American pluralism and inclusion. It would be a political calculation by a desperate man, and I hope—just as desperately—that by now, most voters are past fooling.

Related:

Today’s News

- The judge in Donald Trump’s New York hush-money case delayed his criminal-sentencing hearing until September in light of the Supreme Court’s recent decision on presidential immunity.

- Rudy Giuliani, the former New York City mayor and an ex-lawyer for Trump, was officially disbarred for participating in Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

- Texas Representative Lloyd Doggett became the first sitting Democratic politician to openly call for Biden to withdraw from the presidential election after his debate performance.

Dispatches

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

My Life Depends on Playing Chess 40 Times a Day

By Cory Leadbeater

For the past half decade, I have found myself playing nearly 40 games of chess every day. I still work a full-time job, write fiction, raise a child, but these responsibilities are not prohibitive. My daughter goes down and I play late into the night, I sleep a bit, then I wake very early to play more. I play during off-hours at work, on lunch breaks, during writing time when I can’t work out a scene, and on Saturday mornings, after feeding my cats and brewing the coffee and giving Alma her egg. Addiction in my life has this quality: Something I was previously not doing at all—drinking, smoking cigarettes, collecting coffee cans, pulling hairs out of my face one at a time with tweezers—becomes all-consuming.

More From The Atlantic

Culture Break

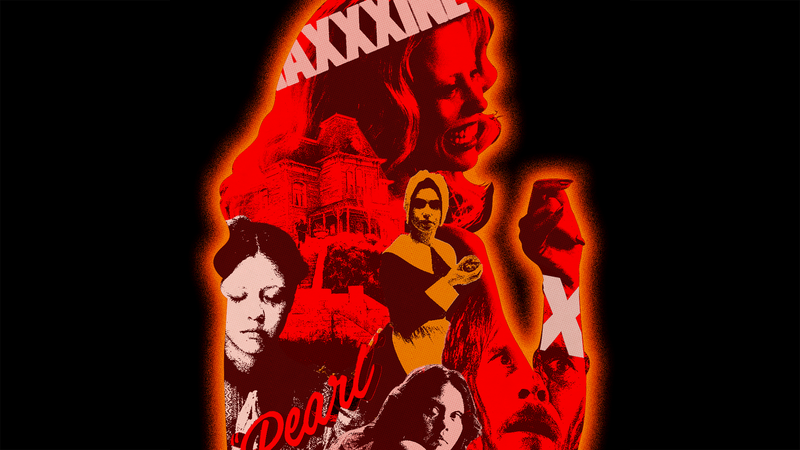

Watch (or skip). MaXXXine (out Friday in theaters) pays tribute to yesteryear’s slasher flicks, David Sims writes. Is that enough?

Read. Paige McClanahan’s debut book, The New Tourist, argues that rather than giving up on tourism, we should just do it better, Chelsea Leu writes.

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)