Fashion

What Jamaican Aesthetics Bring To Fashion | Essence

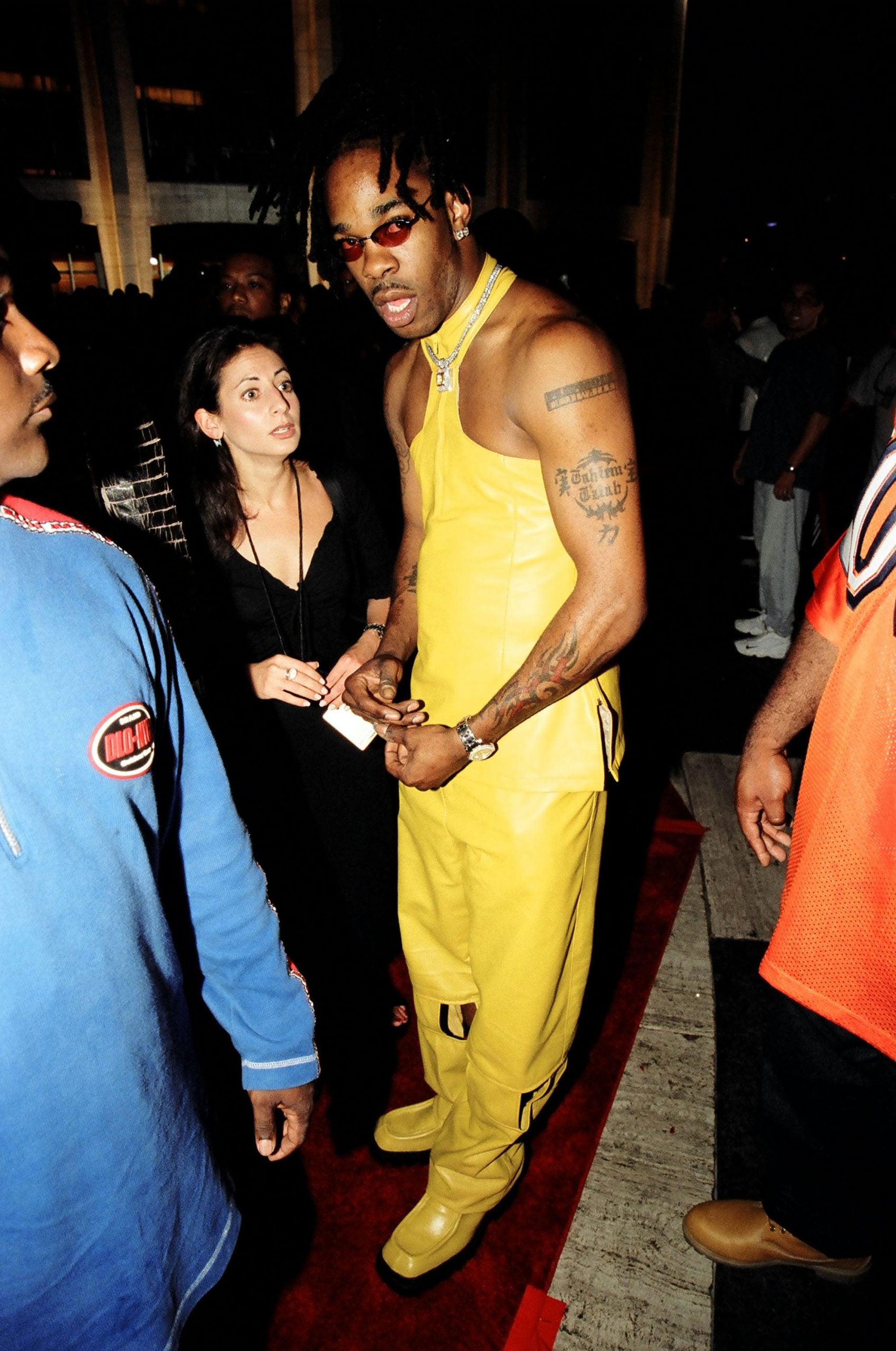

10 years ago, VH1 published an article I used as a source material for a conference talk. It was titled “Is Busta Rhymes A Terrible Dresser Or An Avant-Garde Style Genius?” During the talk, I touched on what journalists were missing in their evaluations of Busta Rhymes’ style at its peak. My argument was, and still is, that his dress was a mirror and negotiation of his Jamaican-American identity. It wasn’t tacky it was his truest self actualized.

Ethnographer Adom Heron writes of Caribbeans’ desire to “assert their individual being in the world” in his essay “An Aesthetics of Play,” which explains Jamaican men’s often flamboyant self-fashioning. He holds that this audacity is linked to and most vividly exhibited within dancehall music. Which is all rooted in an aesthetic philosophy of boldness and transcending the hardships of everyday life.

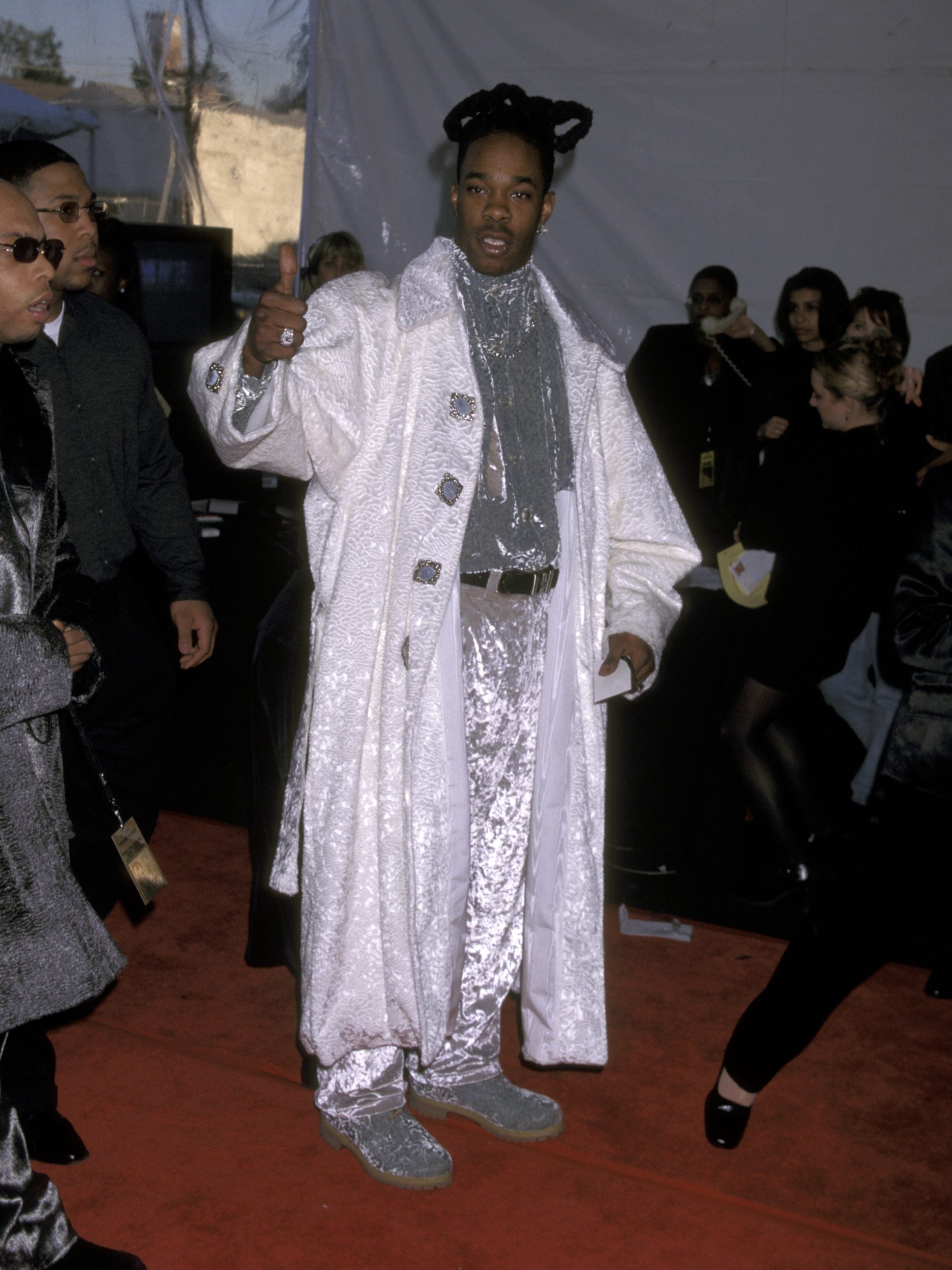

Rhymes was nothing if not bold, often turning up to red carpets in lustrous, loudly-colored, body-revealing clothes. Skin-tight shirts. Clothes that cut close to and away from the body to accentuate his shape but also to transform it. Artful hairstyles. Stacks and stacks of diamond jewelry also alluded to the Busta’s flair for dramatic garments and accessories. The rapper exemplified a kind of “play” that Heron articulates, thanks to his then stylist and costume designer June Ambrose, also of Caribbean descent. But as a rapper in America, he faced criticisms that he may not have on the island his parents grew up on. Sure, Jamaica may be just a four-hour flight from his birthplace of New York, but the expectations of how men express themselves, and how far they go in doing so, differ.

Black American masculinity, in all its glory and appeal and outsize influence, is a tricky navigation. We feel so much due to being confronted with so much, yet we can only say so much. The stereotypical “manly” expressions of our masculinity, that is. Such is the case with how we dress. Oh, and who gets to wear a dress? It only takes searching “Black man in a dress” in Google to see that it apparently shouldn’t be us. At the same time, you’ll find versions of our sartorial language spoken in many parts of the world. Black menswear, at any given moment, more than any other group, is constantly up for celebration, sampling, emulation, and indeed critique.

It’s only recently that men have recovered the courage to dress like a Prince, or a Lenny Kravitz, or then Busta Rhymes, all of whom have bent the rules much less seen in Jamaica. There’s a different kind of freedom that the men there have when they move in their clothes. “It occurs through a propensity towards cultural creativity,” Heron tells me. “In language, in style, and in dress, these cultural forms can inhabit contradictions without them needing to be resolved.” There’s a transgressiveness to it. It blurs the lines.

As Heron articulates—citing tight trousers as a much-worn, contentious garment—dancehall men in particular are known to overstep “the bounds of acceptable male expression.” Which is to admit that there are limitations placed on them. From Kingston, stylist Troy Oraine says: “There are some conservative values that the culture is still grappling with here. We’ve got some work to do.”

Colonization has impacted Jamaicans’ views on what it means to wear certain kinds of clothes, much like in the United States. Because as cherished as Clarks shoes are on the island, their ties to the British symbolize respectability and have therefore been a marker of upward social mobility.

When it comes to gender expression, Heron says: “There’s this surprise when you encounter, for the first time, men in dancehall spaces who appear to be queer in terms of their style and dress, but the words that are coming out of their mouths or the lyrics that they’re singing, push back against a sense of equality in gendered and sexual terms.” Young boys who move and act in ways deemed feminine can expect to be corrected.

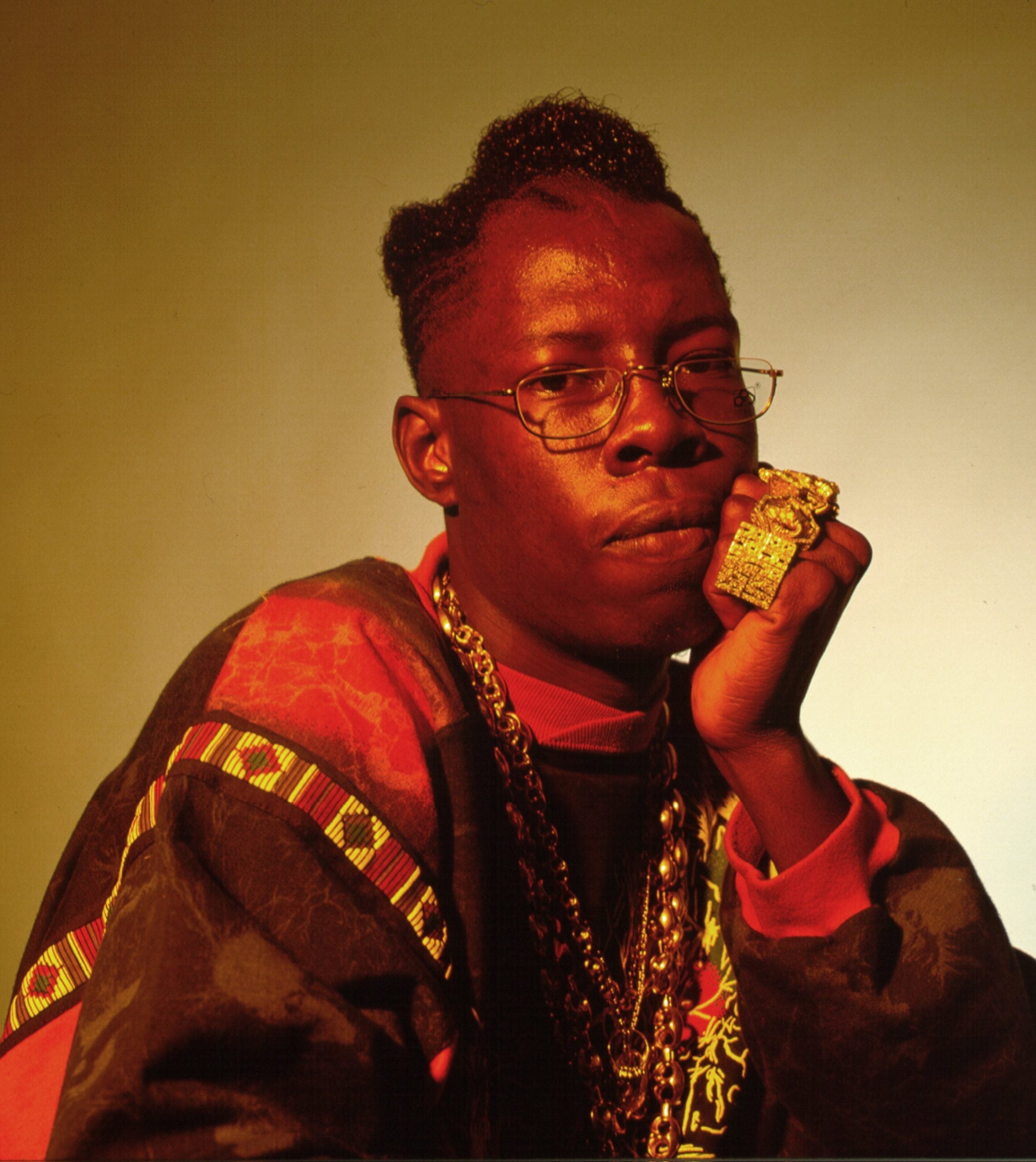

It isn’t necessarily the region’s full embracing of the myriad identities it inhabits that makes it unique, but rather a willingness to accommodate difference. And a proclivity to the spectacular, which we see in figures like Busta Rhymes, turning hip-hop’s dress codes on its head and doubling down on them with his jewels; Shabba Ranks, whose dapper out there appearance originally influenced Rhymes; Slick Rick, who made his eyepatch a personal signature currently on display at The Smithsonian; one of my favorites, Masego, a genre-fusing musician who’s in pursuit of difference but also something more diasporic. Having worked with him in the past, Oraine mentioned how particular Masego is about his wardrobe—a common quality among Jamaican men.

“When people ask me how I got interested in style and who’s my style inspiration, I say it’s my dad because he’s always had a very focused approach to how he dresses,” fashion expert Chrissy Rutherford says of her Jamaican father. “Since I was a kid, I remember he would put on a suit to get on a plane and go to Jamaica. Like, who does that?”

She adds it was always either custom or perfectly tailored. Chalk it up to the shared value of taking pride in one’s appearance across the African diaspora. Part of it is socially enforced, but we also just like to look good. She mentions that among all the gold jewelry he owns, he wears a gold rope chain daily as it remains a style signifier within Caribbean culture.

Jamaican designers based in the U.S. and the United Kingdom are creating garments with a sort of autobiographical flair. The ones deservedly taking over much of the menswear conversation right now are based in England: Martine Rose, Grace Wales Bonner, and Nicholas Daley. But there’s also Theophilio by Edvin Thompson.

Established in 2016, the Brooklyn-based label is vocal about its Jamaican-American approach to design, drawing from the heritage of the founder himself. It is, as the brand’s Instagram reads, “a wearable biography.” It’s a story of dancehall, of New York City, of cultural unity and diversity. It therefore makes suggestions about gender, identities both ethnic and national, expression, and how it all becomes an aesthetic.

Peruse Theophilio’s menswear category and you’ll pretty much find the wardrobe of some of the artists previously mentioned. Shabba Ranks wearing their navy sequined vest with matching gauchos is a given. Bob Marley, a poster child of patriotic swagger, could’ve easily been seen in their striped Rasta lounge pants. Masego would do well to have Theophilio’s pieces fused into his next tour or shoot. And skirts! The brand stocks two A-line skirts—one black leather and the other metallic denim—from their spring-summer 2023 collection, which is included in their womenswear.

Jewelry designer Matthew Harris of Mateo says he takes pride in redefining what the Jamaican aesthetic is, noting that Black visual culture can be over-characterized as bright and heavily printed. His men’s jewelry, similar to his women’s, is elegant and minimalistic. We both agreed that he’s helping to fill a real gap in the market there. But in reflecting upon the style impressions that men in his family have made, he recalls pictures of his dad at the beach in a Speedo and it not being a big deal. He says that Jamaican men might be less anxious about articulating the range of their masculinity, which frees them up to explore more of what clothes can offer.

“There’s multiple layers of bringing oneself to the world, in performative terms and in the creative possibilities of one’s humanity, which is done in a kind of unabashed form in the region,” Heron observes. A lesson on style and in life.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)