Bath Iron Works and many other critical sites on the Maine coast could flood every other week as soon as 2050 without significant changes, a new report concludes. Press Herald file photo by Gabe Souza

Maine won’t have to wait long before it begins to lose valuable coastal infrastructure to high-tide floods.

Forget king tides and storm surges. A new report from the Union of Concerned Scientists predicts sunny-day floods caused by rising seas will hit critical infrastructure as soon as 2030 under a business-as-usual emissions scenario.

“Even without storms or heavy rainfall, high-tide flooding driven by climate change is accelerating along U.S. coastlines,” the report concludes. “It is increasingly evident that much of the coastal infrastructure in the United States was built for a climate that no longer exists.”

Sea levels in Maine are rising faster than ever before, with record-high sea levels measured on the Maine coast in 2023 and 2024. The Maine Climate Council says Maine will experience about 1.5 feet of sea level rise by 2050 and 4 feet by 2100, which assumes we achieve some global emission reductions.

The Union of Concerned Scientists report includes three different sea level rise projections for 2100: 1.6 feet if we greatly reduce emissions, 3.2 feet for a reduced emissions future (assuming intermediate risks, like the Maine Climate Council) and 6.5 feet if we keep emissions rates as they are now.

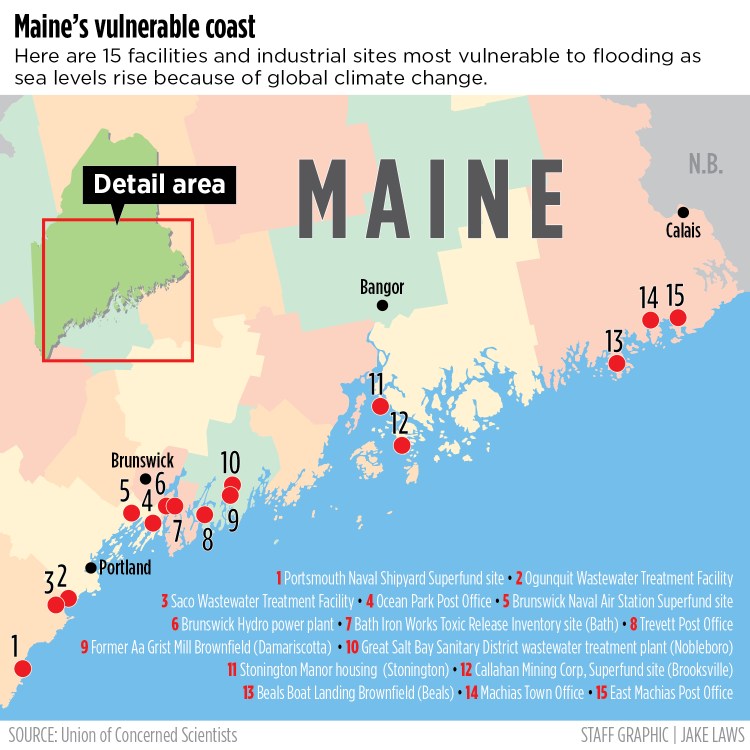

In a business-as-usual future, the report identifies at least six at-risk structures, including a power plant (Brunswick Hydro), a post office (Trevett), two wastewater treatment plants (Noblesboro and Saco) and two polluted industrial sites in Bath, that face the prospect of flooding every other week in just six years.

Critical infrastructure is defined in the analysis as facilities that provide functions necessary to sustain daily life – such as schools, police stations or post offices – or that if flooded could impose societal hazards, such as contaminated industrial sites known as brownfields.

The number of sites at risk of every-other-week high-tide flooding under the business-as-usual emissions scenario increases to 11 by 2050, adding an affordable housing complex, a brownfield, a sewer plant, a post office and Bath Iron Works.

By 2100, the number of sites flooded every other week under high emissions soars to 64 across 31 towns. It includes two town halls (Machias and Long Island), the Bath Police Department, the Lincolnville and Bath fire departments, and Maine Maritime Academy in Castine.

Some owners and regulators of at-risk Maine sites are already taking steps to prepare for the rising seas.

“As a shipyard on a major coastal river in Maine, Bath Iron Works monitors the threats of tidal flooding and rising sea levels,” parent company General Dynamics wrote in its 2023 Sustainability Report. “Bath Iron Works incorporated predicted flood levels in its future facility plans.”

In BIW’s case, not only is it a major regional employer and contributor to the tax base, but it is also one of the at-risk Maine infrastructure sites that release toxic chemicals and pollution, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

On a much smaller scale, Portland businesses in a Marginal Way building facing every-other-week tidal floods by 2100 believe that they will be protected by the huge storage tanks the city built under the ballfields in nearby Back Cove Park. Knee-deep nuisance flooding has forced them to shut down before.

The report urges the state and its coastal communities to adapt and build resilience before it is too late.

Maine doesn’t have as many at-risk coastal infrastructure assets as other U.S. states because it is not as heavily developed, said report author Erika Spanger, director of strategic climate analytics at the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Climate and Energy Program.

But a review of the list reveals that Maine will face shoreline infrastructure risk sooner than many of the other states, giving it less time to begin the lengthy – and often costly – process of planning, implementing and funding its resiliency efforts, Spanger said.

As tidal flooding risks to Maine’s aging infrastructure increase in the decades ahead, Spanger called on policymakers and the public to take urgent action to prepare communities and to sharply curtail the use of fossil fuels, which is the main cause of the climate crisis.

A warming climate caused by the production of heat-trapping gases from the use of fossil fuels causes seawater to expand and ice over land to melt, both of which cause sea levels to rise.

Related Stories

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)