Jobs

June jobs report preview: Beveridge curve implies a balanced labor market as hiring cools

The labor market and inflation have finally come into balance. As Mary Daly, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, said recently, the inflection point where unemployment risks could trump inflation risks “is getting nearer.”

Now, the risk is that as the economy cools, hiring will slow and unemployment may increase.

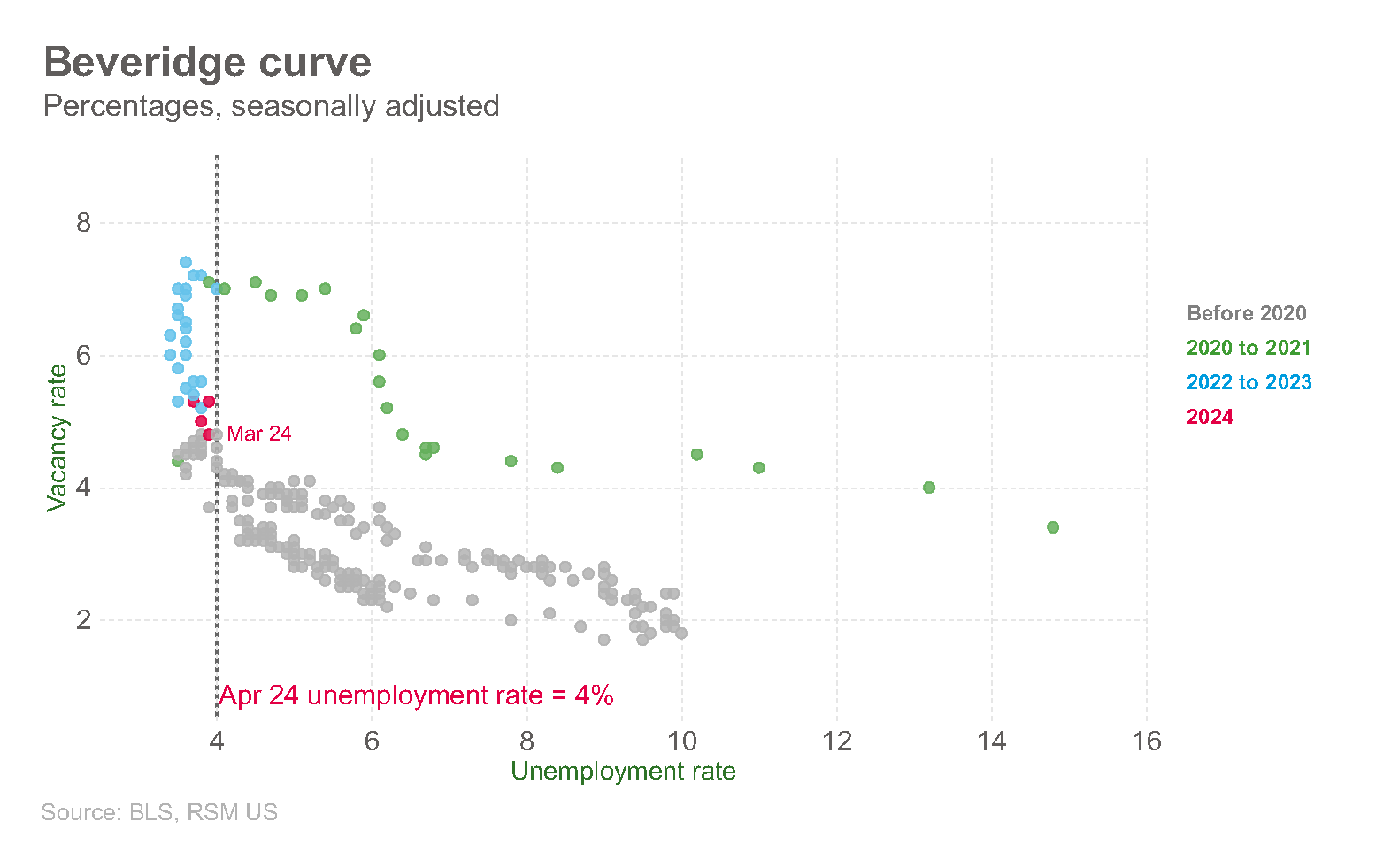

Look no further than a stylized Beveridge curve, which captures the relationship between unemployment and job vacancies and has moved back into balance.

Read more of RSM’s insights on inflation, the economy and the middle market.

That improved balance should be on vivid display inside the U.S. employment report for June when it is released on Friday.

We expect total employment to increase by 190,000, down from 272,000 in May, and the unemployment rate to remain unchanged at 4%. We also expect average hourly earnings to increase by 0.3% on the month, which would translate into a 3.9% increase from a year ago.

The top-line gains implied by our forecast are in line with our estimates of a sustainable and non-inflationary range for job gains, which is between 150,000 to 200,000 on average each month because of the recent increase in the domestic labor supply linked to immigration.

What the data is saying

To determine how tight the labor market has been, we look at five key metrics—the quit rate, job opening rate, unemployment rate, prime-age employment rate and the vacancy-to-unemployed ratio.

To compare the current state of the market with historical benchmarks, we normalize all metrics by calculating their Z-score based on the period from 2001 to 2019 and set all values for February 2020 to 0.

All five metrics are now at or only slightly off their pre-pandemic levels in 2019. For context, in 2019, the year-over-year personal consumption expenditures index—the Fed’s key gauge for inflation—was around 1.5% while the upper bound of the Fed’s policy rate peaked at the same time at only 2.5%.

Now, PCE inflation is at 2.6% while the policy rate is in a range between 5.25% and 5.5%—which means today’s spread between interest rates and inflation rates is almost double what it was in 2019.

The Beveridge curve

We also look at the Beveridge curve, which shows the negative relationship between the job vacancy rate and unemployment rate. After a wild swing during the pandemic, the curve has fallen back to its long-term relationship from before the pandemic.

Note that the elevated job vacancy rate has been one of the Fed’s top targets as it indicates how strong labor demand has been. Now, with the curve back to its steady state, it is much harder to bring down labor demand without pushing the unemployment rate higher.

Policy implications

June’s employment report will be the last jobs report before the Fed reconvenes in July to make its policy decision. The Federal Open Market Committee will most likely be considering the idea of a labor market back in balance as inflation now stands within shouting distance of its 2% target.

That means the Fed should reduce a too-restrictive federal funds policy rate sooner rather than later to avoid unforced policy errors that could unnecessarily result in higher unemployment rates, slower growth and a premature end to the current business cycle.

In keeping its policy rate between a range of 5.25% to 5.5% for almost a year now, the Fed has been relying on a robust labor market and the residuals of trillions of dollars in fiscal support to sustain economic growth.

While the decision to hike rates to such elevated levels was appropriate at the time, we do not see any reason for the Fed not to relax its too-restrictive rate later this year as disinflation continues to take hold.

Most of the key metrics on labor market slack have fallen back to their 2019 level, except for wage growth. But if we factor in the sharp increase in productivity over the past couple of quarters, wage growth is also much closer to its sustainable level.

When we say monetary policies operate with a long and variable lag, that view applies both ways. Our view that the labor market is nearing an inflection point suggests the Fed risks being behind the curve again by waiting too long to act on rates.

But even with the recent encouraging numbers, the Fed is stuck with its data-dependent mantra and forward guidance that do not leave much room for a surprise rate cut in July, barring an unexpected economic shock.

That is why we are calling for the Fed to cut rates starting this September, followed by one or two more cuts in the fourth quarter before the damage to the labor market becomes irreversible.

The takeaway

The resilience of the U.S. economy over the past 12 months has been the result of a strong labor market, residual support from fiscal policy and improved financial conditions linked to optimism over artificial intelligence. Those factors have offset the impact of elevated borrowing costs that are at a multidecade high.

These are factors beyond the Fed’s control and will eventually fade if monetary policy remains too tight for too long. We think it will soon be time for the Fed to cut rates to avoid unnecessary damage to jobs and economic growth.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)