World

India election 2024: How Modi’s rivals came back from the brink

Geeta Pandey,BBC News, Delhi

BBC

BBCThe results of India’s general election announced on Tuesday are being interpreted in a rather unusual way. While the winners appear subdued, the runners-up are celebrating.

The NDA alliance, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has won a historic third term in power, with more than 290 seats in the 543-member parliament.

But his Bharatiya Janata Party on its own did not reach the magic figure of 272 seats needed to form the government – and the prime minister is now being seen as a much diminished leader.

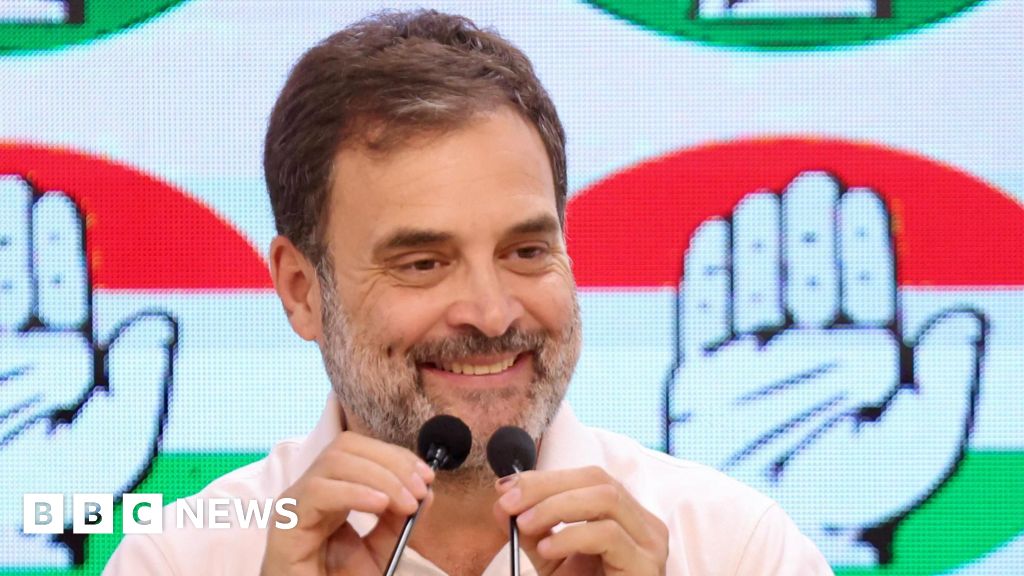

The outcome is being seen as a “huge comeback” for the opposition INDIA alliance and Congress party leader Rahul Gandhi, the bloc’s “unofficial mascot”.

The alliance has won just over 230 seats and doesn’t have the numbers to cobble together a government – but more than 24 hours after counting of votes began, they are yet to concede defeat.

“It’s an extraordinary story,” political analyst Rashid Kidwai told the BBC. “The result is surprising. The opposition has managed to pull off the unexpected.”

A jubilant Congress party called the verdict “a moral and political defeat for Mr Modi”, whose party had campaigned predominantly on his name and record. On Tuesday evening, Mr Gandhi told a press conference that “the country has unanimously sent a message to Mr Modi and [Home Minister] Amit Shah that we do not want you”.

There’s a backdrop to this exuberance.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGoing into the election, the opposition seemed in complete disarray and the Congress-led INDIA bloc, made up of more than two dozen disparate regional parties, appeared to be on the verge of imploding. Experts questioned whether it was fit to challenge Mr Modi, who looked unstoppable at the time.

And as the election neared, the opposition faced an uphill battle. Parties and leaders were raided by government agencies; two chief ministers – including Arvind Kejriwal of Delhi – were jailed; and bank accounts belonging to Congress were frozen by the income-tax authorities.

The credit for the opposition’s performance, Mr Kidwai says, largely goes to Mr Gandhi, the much criticised scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. His great-grandfather Jawaharlal Nehru was the first and longest-serving prime minister of India. His grandmother and father also served as PM.

“He’s a fifth generation dynast and came with a lot of historical baggage,” the political analyst explains. “The mainstream media in India was very hostile to him and social media didn’t take him seriously. He was targeted and projected as a non-serious politician who took too many holidays.”

But, Mr Kidwai says, he overcame the odds and, in recent years, has worked hard to change that impression of himself and his party.

“During his Bharat Jodo Yatra and the Nyay March through the length and breadth of the country, he met millions of people – which added to his stature and won him lots of support. It also gave him confidence and political heft.”

But Mr Gandhi was still not perceived as a threat to Mr Modi. Last year, a court in Mr Modi’s home state Gujarat convicted the Congress leader of defamation. He was thrown out of parliament and barred from contesting elections – until the Supreme Court suspended his conviction.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe perception that the BJP was seeking to diminish its opposition, says political analyst and author Ajoy Bose, backfired.

“The BJP got a bit arrogant and complacent. But their shock and awe tactics to intimidate the opposition worked against the BJP and led to the formation of the INDIA bloc.”

The parties, he says, “were afraid they would be wiped off and many saw echoes of Emergency [a reference to the 1975 action of then-PM Indira Gandhi to suspend elections and curb civil rights] in the way the government was functioning”.

India has “a history of competitive democracy”, Bose says, adding that among the people “there was a sense of disquiet and discomfort about the country turning into a one-party dictatorship”.

As the results show, the BJP juggernaut met strong resistance in several opposition-ruled states.

In Tamil Nadu, the ruling DMK party kept the BJP out by winning all 39 seats in the state. In West Bengal, Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee fought to limit the BJP to 12 seats (Mr Modi’s party had won 18 of the 42 seats in 2019). In Maharashtra, the BJP was limited to nine seats – it had won 23 of the 48 seats in 2019 and its then-ally Shiv Sena had bagged a further 18.

But the biggest upset for Mr Modi and the BJP, Mr Bose says, came from the bellwether state of Uttar Pradesh (UP).

“Akhilesh Yadav and his Samajwadi Party (SP) is the biggest success story of this election. A very clever alliance with Rahul Gandhi won them 43 of the state’s 80 seats. The BJP’s tally has been restricted to a poor 33.” Mr Modi’s party won 62 seats in 2019 and took 71 in 2014.

In the run up to the election, Mr Modi had described Rahul Gandhi and Akhilesh Yadav as “a pair of boys” whose alliance had “flopped” many times in the past. But as the results show, this pair of boys soundly beat the BJP in UP.

“A key takeaway from the election,” Mr Bose says, “is that the grand new Ram temple in Ayodhya city wasn’t enough for the BJP to win.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe party had banked on the Ram Mandir temple to be their trump card, with Mr Modi presiding over the opening of the unfinished temple in Ayodhya with much fanfare in January. But in the Faizabad constituency, where it is located, the BJP candidate lost.

Abhishek Yadav, an SP youth-wing leader and a star campaigner for his party, told the BBC that initially they too believed that the temple would help the BJP win the key state.

“Until early April, [the] election in the state had seemed like a one-sided contest with the odds stacked against us,” Mr Yadav told me recently. “But we sensed there was an undercurrent of resentment against the BJP when large numbers of people started gathering at our rallies.”

People were unhappy about a lack of jobs and high food and fuel prices, he said. Many were also angry with the changes in how army soldiers are recruited.

“With the Congress and SP fighting the election together as part of INDIA alliance, all anti-BJP voters came together to vote for us,” he added.

Mr Kidwai says that – notwithstanding the surprisingly good performance of the opposition – in some ways, it was a missed opportunity, as the INDIA bloc failed to read the voters’ mind and did not sense the disquiet they felt with Mr Modi’s government.

“They spoke about joblessness, rural economic distress and were able to win over many voters – but there were lots of gaps in their strategy,” he says. “The NDA’s third term has come only because of weaknesses in the INDIA bloc. They could have forged alliances in Andhra Pradesh and Odisha and that would have made their tally stronger.”

But now that the NDA – and Mr Modi – are back in power, INDIA needs to institutionalise its alliance and Mr Gandhi, “the chief architect of the alliance”, must lead from the front, Mr Kidwai adds.

“It’s unlikely that the government will stop going after the opposition. But it also can’t be business as usual for the government. They cannot continue with their politics of vendetta; it will have to be toned down.

“The strength of opposition in parliament would allow restoration of functional ties in parliament. There’s great need for coalition politics now. And Congress as the single largest opposition party in the coalition must lead from the front.

“The Gandhis consider themselves as trustees of power, not power-wielders. But now the time has come to change. Rahul Gandhi has to take on the mantle of leadership and lead.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)