Entertainment

Faye Dunaway Described as ‘Scary and Frightening’ in New Doc

Few stars have shone as brightly as Faye Dunaway. At her peak in the 1970s, Dunaway was a leading light in landmark films including Bonnie and Clyde, Chinatown, and Network, which won her an Oscar. Her work generated controversy, but so did her widely reported offscreen volatility.

When you talk about Dunaway, you expect thrilling drama, whether on or off screen. So she is the last Hollywood icon you’d expect to headline a documentary as flavorless as Faye, arriving on HBO on Saturday.

In an age of celebrity memoir—from Britney to Barbra—that emphasizes the all in “tell-all,” Faye paints by numbers, and does not do justice to Dunaway’s singular talent and persona. It doesn’t help that Faye lands on HBO, the home of exhaustive Hollywood biodocs about the likes of Jane Fonda and Steven Spielberg that spent hours unpacking the lives of movie meganames. At a brief 90 minutes, the documentary never gives itself enough breathing room to allow us into Dunaway’s head between the expected career highlights.

Faye is upfront about its subject’s volatile reputation, but evasive on the details that created it. The film instead glides through those passages on an expressway of euphemism—one interview subject refers to the generalized accusations against Dunaway as “superficial comments.” For this film, Dunaway is “difficult” in sculpting her bangs for her interview, in her abhorrence for water bottles over glasses, in her unquenchable lust for Blistex. It’s an avoidance you can’t entirely hang on Dunaway.

The film’s most significant reveal is Dunaway’s bipolar diagnosis, something broached almost as vaguely as the accusations of bad behavior against her. In discussing the situation around her firing from Tea at Five (a play that in its brief run saw Dunaway perform as Katharine Hepburn with reports of physical and verbal assault to the crew, including calling an assistant a “little homosexual boy”), her son Liam O’Neill qualifies her behavior as “her demons got ahold of her” without onscreen follow-up questioning from director Laurent Bouzereau or direct mention of the actress’s actions.

Faye Dunaway Newsweek Cover from 1968.

Jerry Schatzberg/HBO

More shockingly, the documentary doesn’t do justice to the power of Dunaway’s talent. We are served a rehash of oft-repeated narratives—Bonnie and Clyde’s graphic violence, her Network character’s controversial lack of compassion, Roman Polanski yanking a hair out of her head on the set of Chinatown—without enough reverence for how she cemented those roles in film history (even if the work speaks for itself). For her part, Dunaway seems happy to reassert this conventional wisdom, but we can blame the lack of depth on Bouzereau.

Many of the lingering rumors and documented actions by the actress (such as journalist Peter Biskind’s claim in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls that she refused to flush her own on-set toilet) go untouched. Events like the Oscar envelope fiasco and her public spat with Andrew Lloyd Webber over her Sunset Boulevard aren’t mentioned. What remains unfulfilled is the opportunity for the star to explain her point of view, and as a result, Faye fails to enlighten.

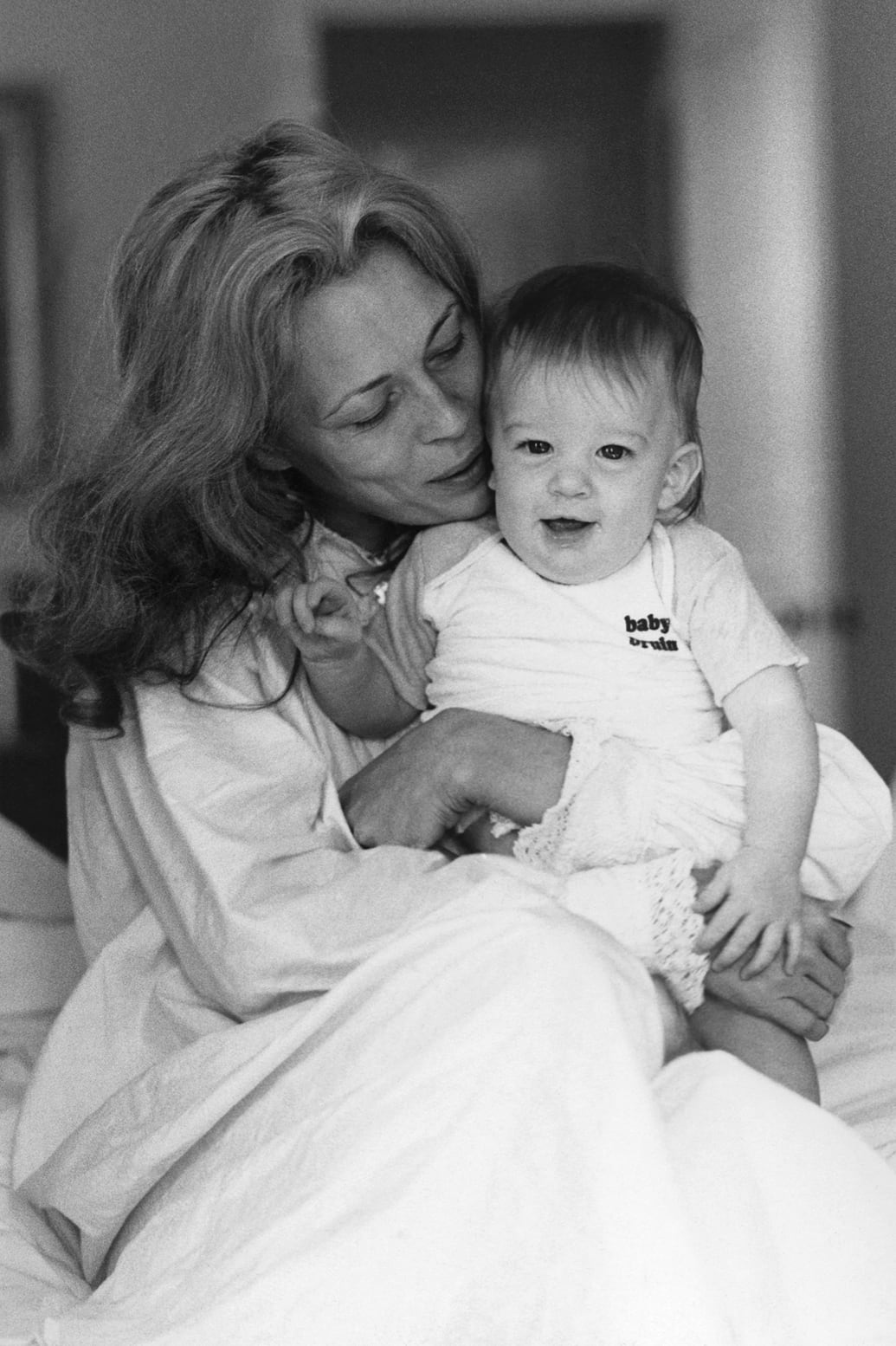

Faye Dunaway and her son Liam in the early 1980s.

Terry O’Neill/Iconic Images/HBO

Perhaps the only way that Faye affords Dunaway the chance to set the record straight is how Mommie Dearest doesn’t prove to be an off-limits topic. Legend tells that Dunaway refuses to talk about the film and her performance as Joan Crawford due to the critical drubbing it received and its ironic cult fandom. However, the documentary disputes that reputation, with Dunaway seen discussing the film then and now, even if she remains unchanged in considering the film a mistake.

The subject of Dearest allows some complexity to slip through the cracks of the documentary’s glossy veneer, including the closest the film comes to actually citing Dunaway’s misbehavior. In an onscreen interview, Dearest costar Rutanya Alda describes Dunaway as “scary [and] frightening,” intimating that director Frank Perry feared having to fire her should she look better than Dunaway. This is immediately contrasted with Mara Hobel (who played Dunaway’s onscreen daughter and receiver of Crawford’s dramatized torment) describing a loving working environment with her costar and tearfully lamenting that the film could be so nuclear for Dunaway. It’s fleeting, but it’s a glimpse of the more candid and comprehensive portrait that an icon of Dunaway’s stature deserves.

Dunaway is less guarded when discussing her connection with her son. Their relationship is where Faye finally shows us something we don’t already know, with the star showing more vulnerability when discussing her child than her other biodoc contemporaries have allowed themselves. It’s a fascinating relationship, with Liam presented as protector and preserver of his mother’s narrative—though the film’s makers prove too timid to delve further.

In dodging the audience’s most obvious questions, the film only creates more. At this point in her career and diagnosis, it’s understandable that Dunaway would not wish to stoke the embers of past fires, but this leaves Faye feeling remarkably incomplete.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)