Firms that serve as intermediaries to negotiate and control prescription drug access in the US “wield enormous power,” largely with “extraordinarily opaque” business practices, and may be “inflating drug costs and squeezing Main Street pharmacies” for profit, according to a searing interim report released Tuesday by the Federal Trade Commission.

Amid a national focus on America’s uniquely astronomical drug costs, the FTC is taking aim at firms that largely work deep in the bowels of the country’s labyrinthine health care system, well hidden from public understanding and scrutiny: pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs).

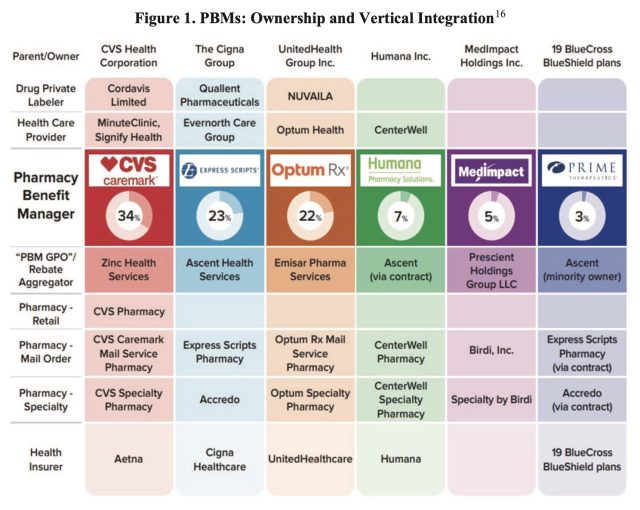

PBMs were initially hired by various payors—employers, health insurance companies, government health plans, and others—to manage prescription drug benefits through various plans. But PBMs have evolved over the years to also negotiate rebates from drugmakers, set reimbursements for dispensing pharmacies, and develop drug formularies (the list of drugs that a health plan covers.) While those functions alone grant PBMs a large amount of power, consolidation and integration over recent years has concentrated that power in troubling ways, according to the FTC report.

The top three PBMs in the country currently—CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and Optum Rx—processed nearly 80 percent of the nearly 6.6 billion prescriptions dispensed in 2023. But these big PBMs aren’t standalone companies; they are integrated into massive corporate conglomerates that encompass some of the country’s largest health insurance providers and also pharmacies, including specialty pharmacies, mail-order pharmacies, and, in the case of Caremark, one of the country’s largest retail pharmacy chains. Most recently, these huge conglomerates have even moved into the business of private drug labeling, partnering with drugmakers to distribute drugs themselves under different trade names.

Gross revenue

In the FTC’s investigation so far, the commission found evidence that PBMs are steering people toward their affiliated pharmacies—hurting small, independent pharmacies—and allowing their affiliated pharmacies to rake in payments “grossly in excess” of average drug costs. For instance, for two generic cancer drugs (one for prostate cancer and the other for leukemia), pharmacies affiliated with the top three PBMs collectively raked in nearly $1.8 billion in revenue from 2020 to 2022. That represents an excess of revenue of $1.6 billion dollars over the national average cost for the drugs. In other words, pharmacies not affiliated with the top PBMs would have otherwise seen revenue of under $200 million for the same drug dispensing.

Further, the FTC found evidence that big PBMs and big brand pharmaceutical companies make agreements to exclude cheaper drugs made by a rival manufacturer from a PBM’s drug formulary in exchange for certain pricing and rebates.

“The FTC’s interim report lays out how dominant pharmacy benefit managers can hike the cost of drugs—including overcharging patients for cancer drugs,” FTC Chair Lina Khan said in a statement. “The report also details how PBMs can squeeze independent pharmacies that many Americans—especially those in rural communities—depend on for essential care. The FTC will continue to use all our tools and authorities to scrutinize dominant players across healthcare markets and ensure that Americans can access affordable healthcare.”

The commission released the report in a 4-1 vote. The two Republican commissioners issued statements expressing concern that the interim report was based on limited data and evidence. The FTC report noted that some of the PBMs have not yet fully responded to orders from the commission two years ago. The FTC said, however, that if PBMs fail to comply or continue to delay, the commission will take them to court.

In a response to The New York Times, Justine Sessions, a spokesperson for the PBM Express Scripts, disputed the FTC’s report. “These biased conclusions will do nothing to address the rising prices of prescription medications driven by the pharmaceutical industry,” she said.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)