Here on Earth, being able to 3D print replacement parts is handy, but rarely necessary. If you’ve got a broken o-ring, printing one out is just saving you a trip to the hardware store. But on the Moon, Mars, or in deep space, that broken component could be the difference between life and death. In such an environment, the ability to print replacement parts on demand promises to be a game changer.

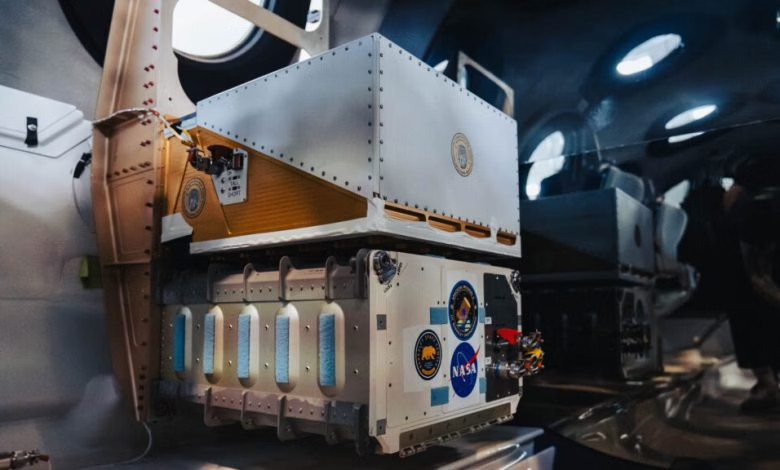

Which is why the recent successful test of a next-generation 3D printer developed by a group of Berkeley researchers is so exciting. During a sub-orbital flight aboard Virgin Galactic’s Unity spaceplane, the SpaceCAL printer was able to rapidly produce four test prints using a unique printing technology known as computed axial lithography (CAL).

NASA already demonstrated that 3D printing in space was possible aboard the International Space Station in a series of tests in 2014. But the printer used for those tests wasn’t far removed technologically from commercial desktop models, in that the objects it produced were built layer-by-layer out of molten plastic.

In comparison, CAL produces a solid object by polymerizing a highly viscous resin within a rotating cylinder. The trick is to virtually rotate the 3D model at the same speed as the cylinder, and to project a 2D representation of it from a fixed view point into the resin. The process is not only faster than traditional 3D printers, but involves fewer moving parts.

Lead researcher [Taylor Waddell] says that SpaceCAL had already performed well on parabolic flights, which provide a reduced-gravity environment for short periods of time, but the longer duration of this flight allowed them to push the machine farther and collect more data.

It’s also an excellent reminder that, while often dismissed as the playthings of the wealthy, sub-orbital spacecraft like those being developed by Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin are capable of hosting real scientific research. As long as your experiment doesn’t need to be in space for more than a few minutes to accomplish its goals, they can offer a ticket to space that’s not only cheaper than a traditional orbital launch, but comes with less red tape attached.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)