Bussiness

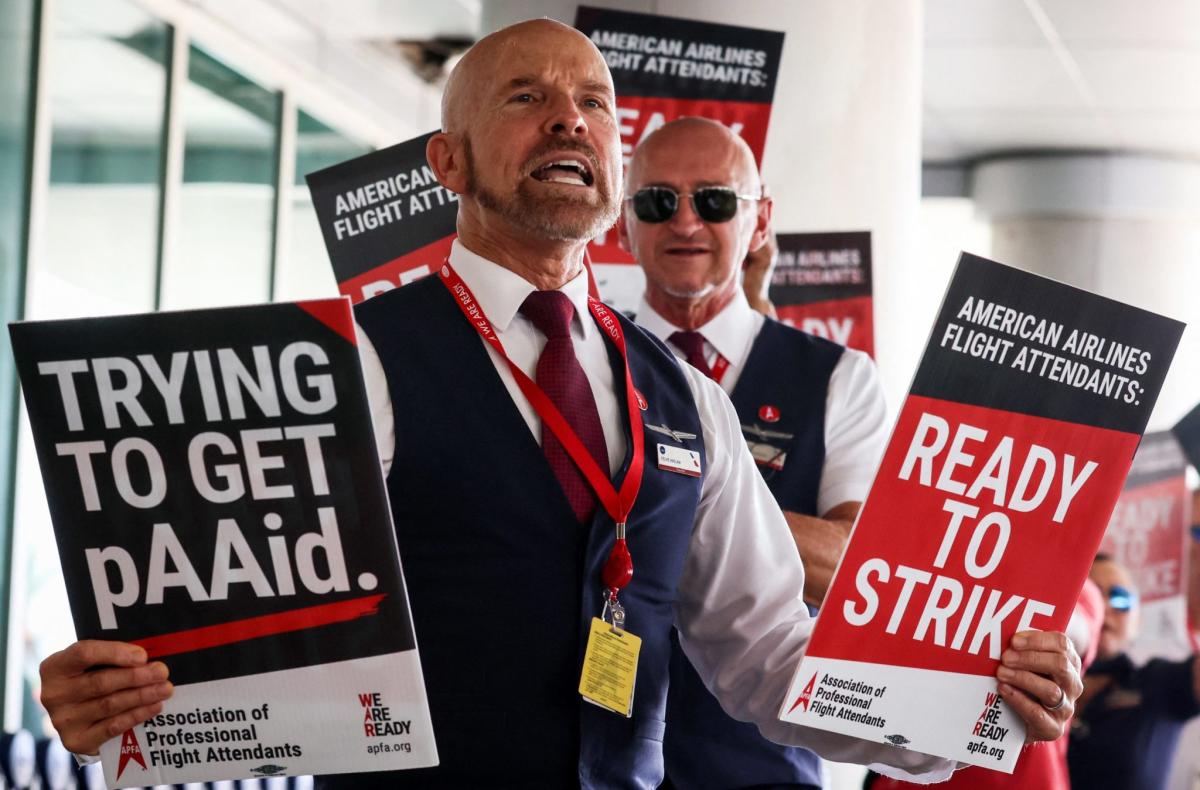

American Airlines flight attendants say their pay is so low, they fight for airplane meals to save money and sleep in their cars—and they’re ready to strike

American Airlines recently offered to hike flight attendants’ pay 17%—but the workers say that won’t be enough to stop the first airline strike in 15 years.

As the airline and its attendants negotiate, American CEO Robert Isom this week sent a video message offering a 17% wage increase, just enough to push new Boston and Miami flight attendants above food stamp eligibility.

The airline said the pay increase would take effect immediately and claimed it is not “asking anything from the union in return,” an unusual move, Isom said in the video message, which was confirmed by an American Airlines spokesperson. “But these are unusual times.”

Still, the Association of Professional Flight Attendants (APFA) rejected the offer, calling it a “PR move” ahead of strike negotiations that will take place between American Airlines and the union next week.

Inflation surges, pay stays flat

APFA and American Airlines have been in negotiations over a new contract on and off since the previous one expired in 2019, APFA President Julie Hedrick told Fortune.

“We’re behind on everything,” Hedrick said. She cited low wages and low pay for food expenses on trips as the most pressing issues. When flight attendants go on domestic trips, they receive an additional $2.20 an hour for food expenses; for international flights, they receive $2.50. These numbers are “very behind” what food actually costs today, Hendrick said.

Since 2014, when the previous contract was negotiated, flight attendants have been left with measly starting salaries even as inflation has shot up 33%, Hedrick said According to an employment verification letter from American, which circulated on Reddit a few weeks ago, an entry-level flight attendant can expect to make $27,315 a year, before taxes. (Like many airlines, American pays its attendants only for the time the plane is in the air.Boarding passengers, waiting between flights, and traveling to and from the airport all mean flight attendants typically work about two hours for each “flight hour” they are paid.)

With American’s proposed 17% increase, the starting wage jumps to $31,959 per year, or $35.5 per flight hour. That rate pushes junior flight attendants who live alone above the level for qualifying for food stamps in states like Massachusetts or Florida.

Most new flight attendant hires are required to live in cities like Dallas, Miami, and New York, which have high costs of living that they cannot afford, Hedrick noted.

American flight attendants are sleeping in their cars, she said. Some of them fight for trips just for the chance to eat the plane meals, if the pilots don’t take their meals first.

“Our new hire flight attendants are struggling,” Hendrick said, adding that new hires most strongly rejected the 17% hike.

For these attendants, lagging pay adds insult to injury when seen against the backdrop of the post-pandemic years, which exacerbated longstanding issues in the industry including staffing shortage, long hours, and unruly passengers, some of whom assault airline staff.

That’s leading to record burnout among attendants.

18 months of pickets

“We have picketed for a year and a half, and we’ve done at least 11 pickets,” Hedrick said. “Our flight attendants have demonstrated our resolve and our solidarity to get a contract, an industry meeting-contract that we deserve and we will take nothing less.”

APFA is proposing a raise of 33% — in line with the rise in inflation since 2014—with a cap at $91 per hour during the first year of a new contract, with pay raises for each year after.

An American Airlines spokesperson told Fortune that the video message “represents the latest from American.” They did not answer questions about the proposal or the upcoming negotiations.

Of the 39 separate issues on the table – such as sick leave or crew rest, APFA and American have reached a “tentative agreement” on 25. The other 14 are associated with compensation, expenses, vacations, and other terms of agreement.

100-year law could snarl strike

Union leaders face an uphill battle as they head to Washington next week to negotiate. Airline strikes are exceedingly rare—the last one occurred in 2010, when Spirit Airlines pilots went on strike for five days.

That’s because railway and airline workers are not allowed to strike unless given the green light by federal mediator groups, via the 1926 Railway Labor Act. One such group, the National Mediation Board, will oversee the American Airlines negotiations, and can allow a strike to occur if it finds that the groups are at an impasse. Still, the federal government can also block a strike—as happened in December 2022, when President Joe Biden signed a measure passed by Congress to impose a contract between rail companies and workers that many workers had rejected.

Biden, who has called himself “the most pro-union president” in history, enforced the agreement to avoid an “economic catastrophe” during the holidays, he said at the time. With multiple major railroad companies at threat of a industry-wide strike, the stakes for an agreement were extremely high; $2 billion could’ve been lost every day of a strike.

The stakes for a possible strike at American are less dire, since other major carriers would not be affected.

But American attendants aren’t the only one calling for wage hikes. United Airlines is still negotiating a new contract with their flight attendants. Southwest Airlines, in April, approved a contract that includes pay raises totaling more than 33% over four years. The union representing Southwest flight attendants, the Transport Workers Union, said that it provided record gains for flight attendants and sets an industry standard.

APFA, likewise, is asking for a 33% hike, with raises of 5%, 4%, and 4% for the remaining years of a four-year agreement.

The union has also stated that they will not accept any deal without retroactive pay. Last year, American Airlines awarded pilots $230 million in retroactive pay after negotiations with its pilots’ union.

Hendrick’s message regarding the 17% hike seems to be: We want the whole package, not piecemeal raises.

“Our flight attendants want nothing to do with it,” she said. “They, overwhelmingly, yesterday said, ‘No, we want a contract. We’ve been in negotiations long enough, and it’s time to get this deal done.’”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)