Andrew Cunningham

Two big things happened in the world of text-based disk operating systems in June 1994.

The first is that Microsoft released MS-DOS version 6.22, the last version of its long-running operating system that would be sold to consumers as a standalone product. MS-DOS would continue to evolve for a few years after this, but only as an increasingly invisible loading mechanism for Windows.

The second was that a developer named Jim Hall wrote a post announcing something called “PD-DOS.” Unhappy with Windows 3.x and unexcited by the project we would come to know as Windows 95, Hall wanted to break ground on a new “public domain” version of DOS that could keep the traditional command-line interface alive as most of the world left it behind for more user-friendly but resource-intensive graphical user interfaces.

PD-DOS would soon be renamed FreeDOS, and 30 years and many contributions later, it stands as the last MS-DOS-compatible operating system still under active development.

While it’s not really usable as a standalone modern operating system in the Internet age—among other things, DOS is not really innately aware of “the Internet” as a concept—FreeDOS still has an important place in today’s computing firmament. It’s there for people who need to run legacy applications on modern systems, whether it’s running inside of a virtual machine or directly on the hardware; it’s also the best way to get an actively maintained DOS offshoot running on legacy hardware going as far back as the original IBM PC and its Intel 8088 CPU.

To mark FreeDOS’ 20th anniversary in 2014, we talked with Hall and other FreeDOS maintainers about its continued relevance, the legacy of DOS, and the developers’ since-abandoned plans to add ambitious modern features like multitasking and built-in networking support (we also tried, earnestly but with mixed success, to do a modern day’s work using only FreeDOS). The world of MS-DOS-compatible operating systems moves slowly enough that most of this information is still relevant; FreeDOS was at version 1.1 back in 2014, and it’s on version 1.3 now.

For the 30th anniversary, we’ve checked in with Hall again about how the last decade or so has treated the FreeDOS project, why it’s still important, and how it continues to draw new users into the fold. We also talked, strange as it might seem, about what the future might hold for this inherently backward-looking operating system.

FreeDOS is still kicking, even as hardware evolves beyond it

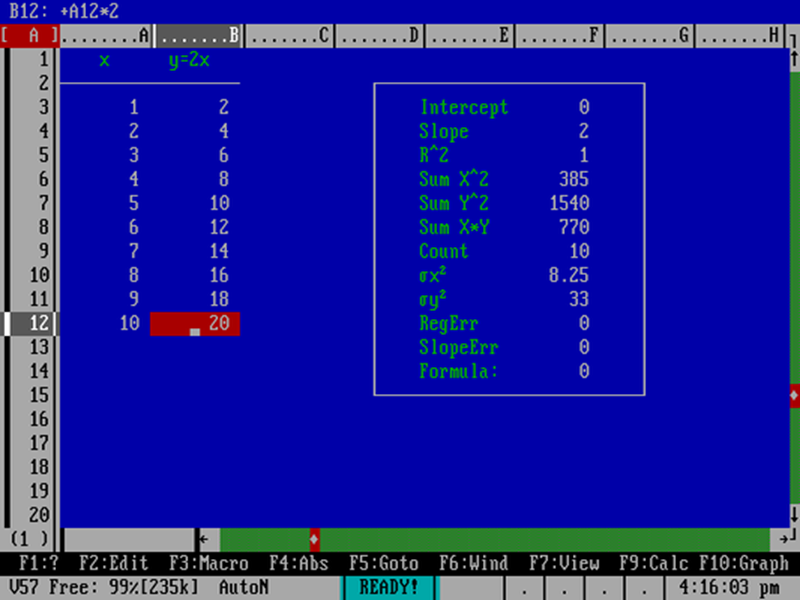

Running AsEasyAs, a Lotus 1-2-3-compatible spreadsheet program, in FreeDOS.

Jim Hall

If the last decade hasn’t ushered in The Year of FreeDOS On The Desktop, Hall says that interest in and usage of the operating system has stayed fairly level since 2014. The difference is that, as time has gone on, more users are encountering FreeDOS as their first DOS-compatible operating system, not as an updated take on Microsoft and IBM’s dusty old ’80s- and ’90s-era software.

“Compared to about 10 years ago, I’d say the interest level in FreeDOS is about the same,” Hall told Ars in an email interview. “Our developer community has remained about the same over that time, I think. And judging by the emails that people send me to ask questions, or the new folks I see asking questions on our freedos-user or freedos-devel email lists, or the people talking about FreeDOS on the Facebook group and other forums, I’d say there are still about the same number of people who are participating in the FreeDOS community in some way.”

“I get a lot of questions around September and October from people who ask, basically, ‘I installed FreeDOS, but I don’t know how to use it. What do I do?’ And I think these people learned about FreeDOS in a university computer science course and wanted to learn more about it—or maybe they are already working somewhere and they read an article about it, never heard of this “DOS” thing before, and wanted to try it out. Either way, I think more folks in the user community are learning about “DOS” at the same time they are learning about FreeDOS.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/roundup-writereditor-loved-deals-tout-f5de51f85de145b2b1eb99cdb7b6cb84.jpg)